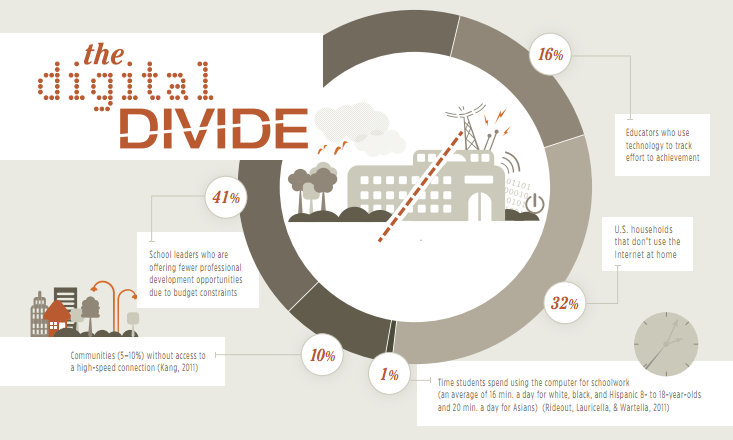

The digital divide is most commonly defined as the

gap between those individuals and communities that have, and do not have,

access to the information technologies that are transforming our lives. The

Pew Research Center’s Internet Project found that internet use

continues to be strongly correlated with age, educational attainment, and

household income. One of the strongest patterns in the data on internet use is

by age group: 44% of Americans ages 65 and older do not use the internet, and

these older Americans make up almost half (49%) of non-internet users overall.

while 76% of adults use the internet at home, 9% of adults use the

internet but lack home access. Groups that are

significantly more likely to rely on internet access outside the home include

blacks and Hispanics, as well as adults at lower levels of income and

education. Poor neighborhoods lack deep penetration of computers and

high speed internet and in many low income African American neighborhoods, this population of older adult, black/hispanic

and low income non users often times constitutes the majority of the neighborhood population.

In poor neighborhoods, only a small portion of households have

any kind of high speed internet access which permits utilization of various

apps, video and other communication tools. Further, poor neighborhoods

typically lack few high speed public access options either. Without this

infrastructure, these neighborhoods cannot deploy internet enabled strategies

that leverage concepts like crowdfunding, the collaborative economy,

and most importantly for rebuilding neighborhoods, web enabled community organizing.

Think about it. Organizing a neighborhood's disparate

people, factions and institutions around common strategies for the neighborhood,

developed through a consensus building process, is extraordinarily difficult. The digital divide becomes even more of a consideration at that point,

since the internet is among the few tools which can connect a widely varying

group of people engaged in a collaborative work across a geography in real time. This

absolutely requires a functional network that can scale as needed.

Its the definition of the internet. The true power of it is that as

a communication network, its unbelievably cheap, enabling

huge information transfer with pretty much zero incremental cost.

But when neighborhoods lack widespread internet access, often coupled with low levels of literacy, none

of this is available. This means that the cost of maintaining the network

of people implementing a neighborhood plan is significant and goes up as the

number of people involved grows. As a practical matter, the network has

to be maintained with high levels of one on one, face to face engagement

(meetings). That kind of network management is scaleable, but only up to

a certain limit given the effort and people resources required. Filling the

gap with volunteers is difficult beyond a certain point.

The indispensable strategic necessity of bridging the digital divide in African American neighborhoods is vividly apparent. Without widespread internet deployment in

neighborhoods, the task of network building and organizing is more difficult,

more expensive and harder to maintain and sustain. Beyond that, second

order effects such as leveraging ecommerce, crowdfunding and crowdsourcing are

largely unavailable as well. These are all creative strategies that

piggyback on the ubiquitous presence of the web.......except when its not.

The cost of being offline is greater now than it was 10 years ago. So

many important transactions take place online, not to mention information

access and commerce opportunity.

What does this mean for community building? A significant

effort at driving investment into African American neighborhoods ought to focus in on bridging the divide so that neighborhoods can better leverage the advantage of an incredibly

cheap, real time global communications and data network. This can and

should take a variety of forms, from digital education efforts to teachyouth how to build mobile apps, to expansion of public access computers andleveraging the deep penetration of mobile, wirelesstechnologies in distressed neighborhoods to move beyond basic access

Indeed, the rise of mobile is changing the story.

Groups that have traditionally been on the other side of the digital divide in

basic internet access are using wireless connections to go online. Among

smartphone owners, young adults, minorities, those with no college experience,

and those with lower household income levels are more likely than other groups

to say that their phone is their main source of internet access. Even

beyond smartphones, both African Americans and English-speaking

Latinos are as likely as whites to own any sort of mobile phone, and are

more likely to use their phones for a wider range of activities.

If we're not working on the digital divide in some form or

fashion, we're leaving on the table one of the most profound and powerful game

changers for our neighborhoods. Let's cross the digital divide.